Nectar yeasts

|

Nectar yeasts |

|

|

|

Click here for picture gallery | |

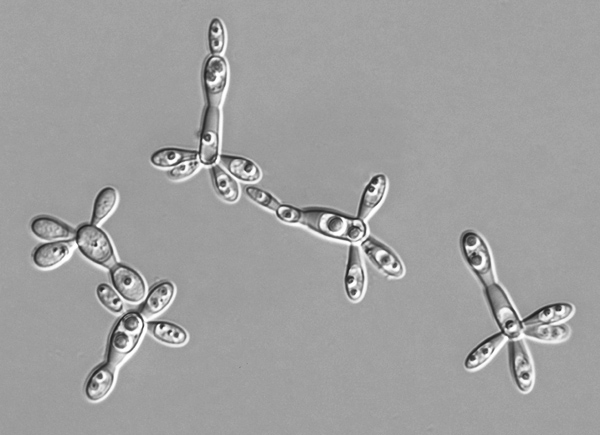

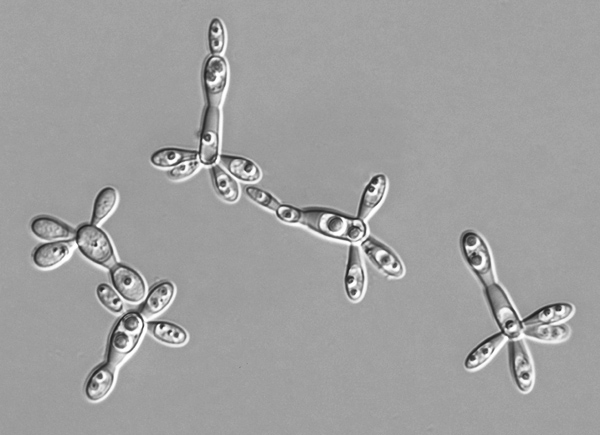

| Cells of Metschnikowia gruessii in floral nectar |

A variety of wild yeasts (unicellular, microscopic fungi) occur regularly in the floral nectar of many insect-pollinated plants, where they can reach extraordinary densities. Cell densities in the order of 103-104 yeast cells/mm3 are commonplace in nectar samples, and densities >104 cells/mm3 are not rare (click here). Our current work on nectar yeasts includes (i) determining spatial and temporal patterns of yeast abundance in floral nectar at a range of scales, including within plant species, among species within habitats, among habitats, and among continents); (ii) finding possible relationships linking these patterns with variation in pollinator composition and abundance; (iii) evaluating the effects of these microorganisms on nectar quality, pollinator behavior, and plant pollination success; and (iv) examining spatial patterns of genetic structuring in nectar yeast populations.

We have found that yeasts occur quite frequently in the floral nectar of many species of animal-pollinated plants in southern Spain, the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico (read more), and South Africa (read more). In a montane forest area in southeastern Spain, nectar yeast communities are characterized by their low species richness, being largely composed of only two species (Metschnikowia reukaufii and M. gruessii). The rest of species, belonging to the genera Aureobasidium, Rhodotorula, Cryptococcus, Sporobolomyces and Lecythophora, occurred very infrequently in nectar samples (read more).

By comparing yeast communities on the glossae of foraging bumble bees (the potential species pool) with those eventually establishing in virgin nectar probed with bee glossae (the realized community), we have been able to show that communities eventually established in nectar are not random subsamples of species on bumble bee glossae. Nectar filtering leads to species-poor, phylogenetically clustered yeast communities that are a predictable subset of pollinator-borne inocula. Such strong habitat filtering is probably due to nectar representing a harsh environment for most yeasts, where only a few phylogenetically-related nectar specialists physiologically endowed to tolerate a combination of high osmotic pressure and fungicidal compounds are able to develop (read more).

Preliminary evidence is revealing that nectar yeasts can be consequential for both the plants and the pollinators that visit the flowers. Variation between flowers in yeast density leads to drastic changes in nectar sugar concentration and composition. At high cell densities, yeasts eventually degrade nectar up to the extreme of depleting virtually all its sugar. Total sugar concentration and percent sucrose decline, and percent fructose increases, with increasing density of yeast cells in nectar (read more). Nectar microbial communities can thus have detrimental effects on plants and/or pollinators via extensive nectar degradation.

Another short-term consequence of the presence of yeasts in floral nectar is that, because of their intense metabolic activity, they warm the flower interior of some winter-flowering plants. This modification of the floral thermal microenvironment may be consequential for the plants by influencing the behavior of pollinators. In flowers exposed to natural pollinator visitation, the temperature excess of nectaries was related to yeast cell density in nectar, and reached +6ºC in nectaries with the densest yeast populations (click here for further reading).